Editorial note: The following piece originally appeared on Verfassungsblog | On Matters Constitutional. We carry it here with kind permission from the author.

Two weeks ago, on a Friday night, I was grabbing a bite to eat with a few Romanian colleagues at Bill’s Restaurant on Green Street in Cambridge, England. Two of us stepped outside for a cigarette. Mid-conversation, someone stopped and started yelling at the top of his lungs: ‘This is f*****g bullshit. I can’t believe it.’ We thought his indignation must have to do either with our smoking or the fact that we were speaking Romanian. We concluded it was the latter.

Romanian and Bulgarian nationals, labelled A2/EU2 migrants since 2007 when Romania and Bulgaria joined the European Union (EU), have a long history of labour discrimination in Britain.

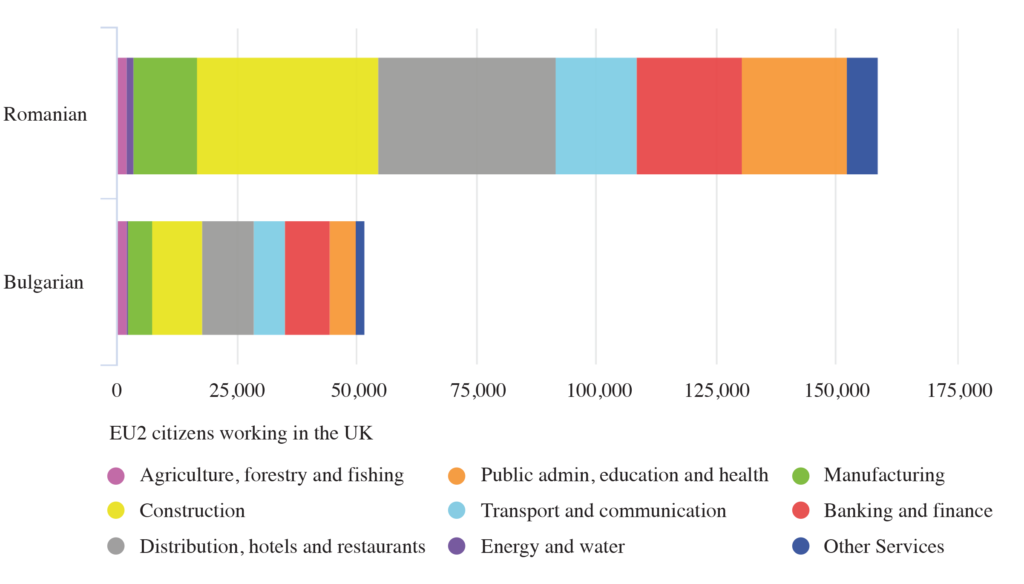

On October 17, 2006, the EU Council confirmed the ascension of the two states to membership in the Union. The United Kingdom (UK) promptly imposed transitional migration limits aimed at preventing Romanian and Bulgarian nationals from freely accessing domestic labour markets for a period of seven years. EU2 nationals could only work under self-employed arrangements and were confined to specific sectors of the labour market, primarily construction and hospitality. As a result, A2 immigrants were consigned to a liminal conditional status as precarious workers, allowed to work in only some sectors of the labour market and excluded from the workplace rights and benefits available to British and other EU citizens.

A2 nationals working in the UK by industry of employment

*Source: UK Office for National Statistics.

Workers’ rights for British workers

The latest UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement was signed on October 19th and has not yet been ratified by the UK Parliament. It will most likely determine the outcome of the upcoming British general election scheduled for December 12, 2019. The Agreement led to public concern that regulations governing workers’ rights would be loosened after Britain’s separation from the EU. Completely left out of the public reaction, however, was any discussion of just who are the workers who would be most affected.

The British labour market is not homogeneously populated by British workers. And most of the A2 nationals currently working in the UK, estimated to be about half a million, will most likely continue to live there: their right to permanent residence is guaranteed under Article 15 of the Withdrawal Agreement, as long as they have legally resided in the country for a cumulative period of at least five years before and during the transition period.

No provisions to counter discrimination

Article 24 of the Withdrawal Agreement addresses workers’ rights post-Brexit. There are several limitations, however, that fail to guarantee that A2 nationals will not suffer discrimination in the labour market.

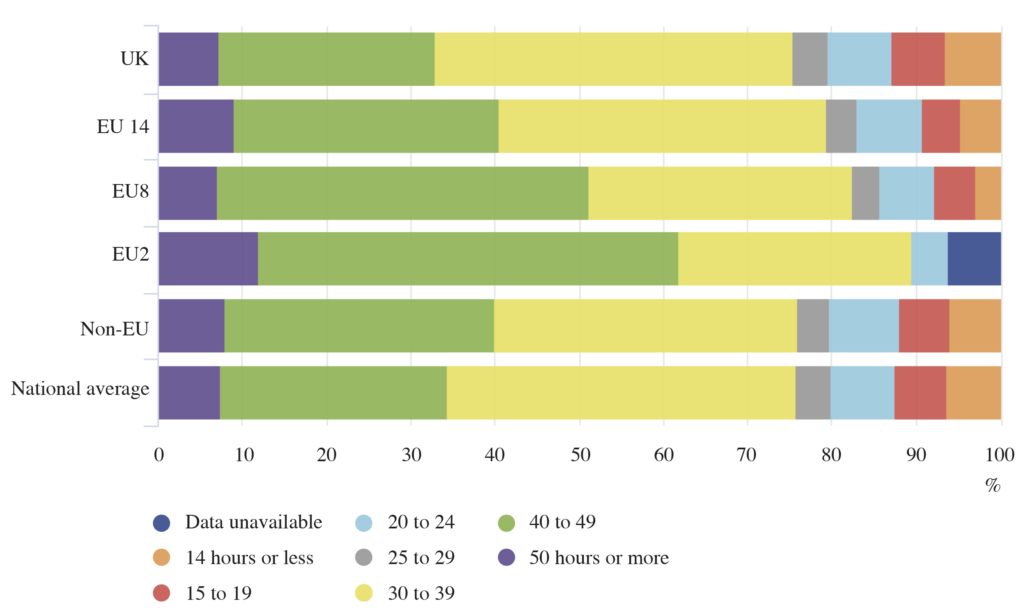

First, under Article 24, 1(a), while ‘the right not to be discriminated against on grounds of nationality in regard to employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment’ is clearly stipulated, there are no specific provisions that would directly prohibit such forms of discrimination. Statistically speaking, 61% of A2 nationals in the UK are already employed in low-paid work, compared to 43% of British nationals. In relating workforce flexibility (i.e., contractual, casual and insecure employment) to nationality, workplaces with an all-British workforce seem more secure and stable, and able to provide higher levels of worker autonomy, as well as shorter work hours. National statistics show that 61% of A2 migrants work more than 40 hours a week, compared to 32% of their British counterparts. In fact, out of all the nationality groups classified by the UK Office of National Statistics – UK, EU14, EU8, EU2 and Non-EU – Romanian and Bulgarian nationals seem to be putting in the highest number of working hours per week.

A2 nationals’ weekly hours of work

*Source: UK Office of National Statistics.

These numbers show that A2 nationals represent a group of workers needing stronger state support than British nationals. Yet the EU-UK deal provides no guarantees that such labour market divides will not be further entrenched during and after the Brexit transition period.

No guarantees of social benefits

Second, under Article 24, 1(d) ‘the right to social and tax advantages’ is left undefined. Hence it is unclear if a tax advantage refers to deductions and exemptions, or to wider social benefits such as child-care assistance. Child benefits payments for 2015/2016 show Romania, for example, to be the second highest receiver, after Poland, with 60,000 claims. EU2 benefit entitlements totaled £25 million for Bulgarian nationals and £80 million for Romanian nationals already residing in the UK in 2015/2016, and £8 million for Bulgarian nationals and £37 million for Romanian nationals who entered the UK in 2015/2016. Yet there are no provisions in the EU-UK Agreement to guarantee that such social benefits will continue to be accessible to A2 workers and will not be restricted to British nationals.

The rhetoric of saving money by restricting benefit claims was a strong point in the Leave campaign that preceded the Brexit vote. During the 2015 UK-EU negotiations, David Cameron proposed capping EU migration numbers, especially those of A2 nationals; imposing a minimum residency requirement of four years to qualify for social assistance benefits; and restricting EU workers’ child benefits to families with residency in the UK. Social and tax advantages were a contentious point in the campaign before the Brexit vote, and should be equally addressed post-Brexit.

The Brexit vote was a vote targeted against A2 migrants. Yet A2 workers in the UK have been left out of not just the underhanded Brexit negotiations, but even Labour Party discussions on employee rights within the British workforce.

A2 nationals might not be British workers, but they are nevertheless workers. And both the EU and the UK have an ethical responsibility to outline provisions so that Brexit does not further marginalize the very same group of workers who already face discrimination in the British labour market.

Raluca Bejan is an Assistant Professor at St. Thomas University, Fredericton, NB, Canada, where she teaches courses in social policy and social movements.