In what follows, we have republished a chapter from Ilya Budraitskis’s new book, Мир, который построил Хантингтон и в котором живем все мы (The World Invented by Huntington in which We All Live. Moscow: Tsiolkovsky, 2020), following a review of the book by Vasily Kuzmin (translated from the Russian by Rossen Djagalov). Many thanks to Giuliano Vivaldi for the translation of Budraitskis’s own text and to the internet journal e-flux, where Vivaldi’s translation first appeared. Kuzmin’s review is available in Russian at the bottom of the page.

Vasily Kuzmin’s Review:

The Tsiolkovsky publishing house just brought out the new book of our comrade Ilya Budraiskis. It is a study of conservatism, starting from the emergence of this tradition to its concrete expressions in Russian society. Indeed, the reader will be particularly interested in the latter. Today’s conservative turn in Russian society represents a fascinating combination. Having originated on the ground of neoliberal reforms, it has shifted its rhetoric since then. If its initial discourse was about some “normalization” and the overcoming of the consequences of “shock therapy,” then towards the beginning of the 2010s this was no longer necessary.

After the Bolotnaya protests the Putin regime was forced to seek a different ideological legitimacy. It was precisely the regime established the famous “spiritual foundations (“dukhovnye skrepy”), on which it still rests and proclaimed the imperative to defend the god-given Russian state from the assassination attempts of the revolutionaries, led by the evil West. “The silent majority,” in this logic, supports the state, assisted in this by the new conservative morality and culture. But there are problems with this morality. Ilya points out that even after proclaiming patriotism and homophobia, patriotic bureaucrats still send their children to London whereas Orthodox members of Parliament are having fun in private gay parties.

The author’s term “anti-revolution” is also very apt. This is the most precise characterization of the state ideology of the Russian federation in the next decade. It is precisely anti- rather than counter- since the latter assumes some new and social forms.

The paradox lies in the fact that the weaker the chances of a revolution, the more virulent is the state’s fear and repression. And it’s perfectly possible that its thoroughly exaggerated and inadequate cautionary measures will lead to a result completed opposite to the one intended.

The attention to conservative Russian values reached its peak during the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Indeed, Huntington enjoyed a resurgence at the time: in his Clash of Civilizations, he predicted the division of the world into eight civilizations, defined by political culture and religious-ethical norms. To Russia he assigns the role of a core state of the aggressive “Orthodox civilization.”

For Huntington, such civilizational belonging amounts the most stable of properties. But after the peak there inevitably comes a decline. The commercialization of education and medicine, the pension reform, the sovereign internet and other “presents” to the population are clearly not helping the regime’s stability. Russia’s president is not opposed to playing the role of the eternal authoritarian leader.

The world Huntington invented has become the world Putin inhabits. Will the readers also want to live in this world, closing their mouths with conservative ideological pacifiers—this is the question that the author leaves us with. To understand the nature of the enemy is to get a trump card in the struggle with him. This is why Ilya Budraitskis’s book is so important and necessary reading for anyone who doesn’t want to accept the current status quo.

Ilya Budraitskis, “What Can We Learn From Vampires and Idiots,” from The World Invented by Huntington, in which We All Live:

The German socialist August Bebel once called anti-Semitism “the socialism of fools.” A fool from the lower classes, the thinking went, indignant at the existing state of things but unable or unwilling to locate the real source of his unhappiness in the capitalist mode of production, instead found a facile but false target in the Jews. The result of this fool’s bad decision would prove catastrophic: instead of joining the ranks of socialists, he became their fiercest and most dangerous adversary. “Socialist foolishness” merits neither indulgence nor understanding. It is, moreover, a formidable weapon in the hands of elites, who are wise enough to know how to exploit it.

This kind of connection between the foolishness of the lower classes and the devious resourcefulness of the upper strata is not unique to the massive fascist movements of the twentieth century. We are talking about here is something more complex and multifaceted, which possesses a tremendous ability to adapt to the new circumstances faced by the conservative spirit today. This style of thought linking the upper and lower stratas is making electoral breakthroughs once again, like those of Trump in the Republican primaries in the US, the Brexit vote in the UK, and parties such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in Europe.

A film still from Martin Scorsese’s 1976 “Taxi Driver” shows Travis Bickle at a rally.

It has become a commonplace to say that support for such phenomena is a manifestation of protest. Astute observers are ever ready to discover hidden rational causes behind these irrational electoral expressions: the downfall of the welfare state, distrust of the establishment, or the consequences of austerity policies. However, when the radical Left invokes these grievances, it falls on deaf ears. But when they are reflected through the distorting mirror of conservative rhetoric, they strike a resounding chord.

This protest is expressed through a melancholic striving to recover something lost—to return to and repeat, through a disgruntled vote, a certain lost idyll. The global party of this “idiotism” (that is to say, political ignorance and civic inadequacy) is opposed today by an Enlightenment coalition of the political mainstream, the media, and a large section of the left-liberal public, who are all inclined to support the “lesser evil.” A conservative, reactionary wave is undoubtedly a significant evil, because it launches its offensive at the level of meanings and values: isolationism instead of openness, racism and sexism instead of tolerance and respect, coarseness and authoritarianism instead of pluralism and a culture of dialogue. The correct choice in each of these oppositions, it would seem, is clear to everyone who is not a complete idiot. But the masses of the “unenlightened,” the ill-mannered, and the irrational are growing, and their leaders have scored a series of victories—as though they know something about society and its future that is inaccessible to those in the enlightened coalition.

This figure of the sinister conservative subject who knows enlightened society better than it knows itself was a significant presence in the historical Enlightenment during a long stretch of its history.

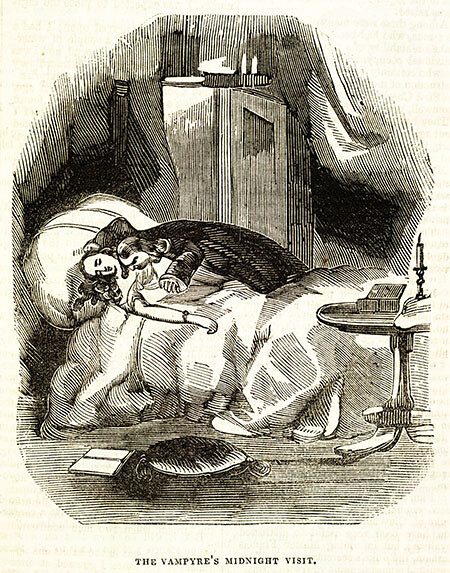

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the figure of the vampire emerged in European culture at the same time as the birth of political conservativism. This vampire, first appearing in the pages of a well-known novel by John Polidori, was completely unlike the insurgent corpse of today’s popular superstitions. The new vampire was a Byronic beauty, an intellectual, and an aristocrat whose easy prey were the naive, enlightened representatives of high society, for whom there existed nothing beyond the limits of a rational, knowable world. The vampire carried out its attacks with impunity, existing on the frontier between the rational world of the living and the irrational world of the dead—the latter having been denied and displaced by the Enlightenment.

An astute representative of the retreating pre-bourgeois era which the bourgeois could not completely bury, the aristocratic vampire posessed the secret of its unconscious. He alone was capable of revealing the contingencies of the Enlightenment’s triumph, its hidden ambiguities and limitations.

An illustration from Varney the Vampire; or, The Feast of Blood (1845–47).

Such were the first astute conservative critics of the French Revolution, such as de Maistre and Burke. They did not deny the Revolution itself—did not doubt its significance as a colossal transformation. Indeed, for them it signified something greater than it did for the revolutionaries themselves. These critics were able to discern how the revolution conceived of itself (i.e., as the triumphant victory of reason over prejudice) and posit its place in an enduring history which was essentially represented as a grand conglomeration of prejudices. Behind the illusion of the triumph of freedom, the conservatives saw dependence on, and restraint by, circumstances.

Marx also began his critique of the Enlightenment with a diagnosis of a fatal rupture between the actual significance of the era and its ambitious self-conception. The progress of the human spirit, the realization of freedom in a state governed by the rule of law, and a democratic republic were an illusion for him too—that “German ideology” behind which was hidden the unknowable abyss of reality: the social relations of labor and capital.

The bourgeois fully realized his potential as an active citizen with inalienable rights. But this realization served only to cover up his real inner schism and his alienation from himself. Behind the illusory legal and political order was hidden a great disorder: the anarchy of production, a hitherto unprecedented stratification of society, and the bewilderment of the individual enduring isolation and vulnerability.

Thus the reign of a conceited instrumental bourgeois reason was threatened by dangers emerging from two ghosts: the vampiric conservative aristocrat, embodying the unvanquished power of prejudice; and the ghost of the worker, the authentic producer of life driven out from politics and invisible to the state. Both of these ghosts were deprived of power and recognition, remaining in a twilight zone concealed from reason, and constituting a lethal danger. From time to time they would make their presence felt with headlong dashes into modernity.

With their critique of the Enlightenment and revolution from diametrically opposed positions, Marxism and conservativism opened up a long and still incomplete dialogue. The participants in this strange dialogue never realized this themselves; they thought they had nothing to debate and nothing to share.1 But sometimes, at moments of acute social crisis, these two displaced ghosts of the capitalist world have materialized and entered the stage of history to engage in deadly combat (as was the case in the first half of the twentieth century). Both Marxism and conservativism see, beyond the illusory capitalist order, a colossal disorder—a chaos whose endlessly accumulating “ruins” were observed by the Benjaminian “angel of history” as it hurtled toward the future.

At moments of oncoming crisis, such as the one we are living through today, this state of catastrophic disorder and disarray becomes evident to many. The masses are gripped with yearning for a genuine order in which everyone can feel confident and have a valued role. Marxism and conservativism give two distinct and fundamentally incompatible answers to the question of how society can find its way forward. Marxism proposes the path of cooperation, self-organization, and self-discipline, while conservativism proposes the path of the leader figure and the restoration of the “ethical state” that disciplines the chaos of personal interests. We can conceive of these as two different interpretations of the Machiavellian Prince—the “Prince” of Lenin and Gramsci versus the “Prince” of Mussolini and Gentile.

In our time, amidst the ever more discernible ruin of society, the political reason of the bourgeoisie attempts to restore itself by mobilizing the ideology of the (liberal) values of individual self-fulfilment and freedom of choice. Indeed, the Brexit “remain” campaign and the ongoing presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton constantly repeat liberal mantras: “everything is in order,” “it’s not all that bad,” “the important thing is to remain reasonable, not to slip into idiocy.” For only a fool would fail to believe that everything is getting better in this best of worlds.

While the liberal establishment drones on about the need to defend Enlightenment values, conservatives play the troublemaker, subverting morality and casting off all decency. It’s not hard to see that the resounding success of Trump is based not on rhetoric about the family, morality, and tradition, but on an aggressive and rousing cynicism. Trump and other insurgent conservatives do not observe the rules of etiquette or maintain the illusion that nothing special is going on. On the contrary, they are an embodied testimony to the fact that things are far from well and that everything is going to the dogs. The advantage that this cynical, insurgent conservatism has over traditional conservativism—which continues to observe the rules of the game of conservative values—was evident in the Republican primary debates, where Trump trounced the other conservative candidates, who clung to moralism and religion. The conservative cynic calls things by their real name, undermining the illusion of stability.

It’s worth noting that Vladimir Putin, whose mutual sympathies with Trump are well known, also owes the popularity of his public image not to his loyalty to “Orthodox traditions,” but to his cruel realism and cynical jokes. In Putin’s Russia, state policies pertaining to moral discipline (e.g., the state’s official homophobia, its limits on abortion rights, etc.) serve not to restore “traditional values,” but rather to elevate the general level of cynicism. Patriotic bureaucrats send their children to study in London while Orthodox deputies enjoy themselves at private gay parties. They are permitted to do what they condemn others for doing—for the simple reason that they are on the highest rung of the social ladder. This is the “naked truth,” for which all the hypocritical acts of the ruling class serve as a demonstration. In order to prevail over modernity, conservatism needs to tear off its moral veil and bring into the open any tacit inequality. Conservatives must force everyone to reconcile themselves to this very real inequality as the only lawful reality—this is the historical task of the conservative. An authentic conservative moral revolution, a real return to the greatness of the idyll of yesteryear, can be carried out only when the ethics of the Enlightenment are turned inside out and buried. One can say that this insurgent, cynical conservativism is the political consequence of the neoliberal era. It turns historical materialism on its head, calling for us to recognize the actual relations of domination and submission not in order to change them, but to reconcile ourselves to them once and for all.

The historical socialist movement, basing itself in the working class, has also staked its existence on the dominant bourgeois morality. While conservatives unmask formal equality for the sake of formal inequality, socialists expose it for the sake of actual equality. However, the social catastrophes and political defeats suffered by the Left in the twentieth century have deprived it of such an assertive antimoralistic position. Today the Left is mainly disposed to cling to a transparent politics of values, thus ceding to conservatives the role of troublemaker. Incidentally, the short-lived success of Bernie Sanders’s campaign was owed precisely to his penchant for agitating against the political elite and stiring revolt, constantly using seemingly outmoded words—such as “socialism” and “revolution”—which nonetheless fired the imagination of his supporters.

An illustration by theartofrichie of Twilight character Edward Cullen, as found on Deviantart. Twilight, a chaste vampire story, was written by Mormon author Stephenie Meyer.

A new type of elite hegemony, based on unabashed cynicism and a revolution against morality, is leading an offensive on all fronts, using fear as its main weapon. This elite hegemony appeals not only to the fear felt by ordinary people—a fear of isolation and helplessness in a ruthless world. It also appeals to the fear felt by the enlightened and the wise, who are terrified of being ruled by idiots. For the enlighted, it appears that their sole option is to choose the “lesser evil.” Striving to defend themselves from the oncoming madness, they cling to any hope of preserving the status quo, convincing themselves and those around them that everything is under control, that reason will somehow prevail. This fear helps conservatives disarm their primary and most dangerous foe.

Intelligent people retreat to small defended territories: academia, the left and liberal political wings, the world of contemporary art. Their knowledge, their critical tools, their ability to reason are now directed towards preserving illusions rather than tearing them down.

In order to recognize our actual situation and to challenge the dominant ideology, we should listen, as in olden times, not to liberals but to conservatives. There is no point in demanding that idiots overcome their own idiocy. Instead, it is perhaps necessary to recall that “this demand to change consciousness amounts to a demand to interpret the existing world in a different way, i.e., to recognize it by means of a different interpretation.”2

The Left can defeat the open cynicism of insurgent conservatives only by going even further than them in critiquing a concealed liberal cynicism. In an era when political correctness leads only to ruin, there is no need to fear being coarse and confrontational. Above all, we must speak more often and more loudly about socialism—after all, fools, in actual fact, are desperately in need of it.

Translated from the Russian by Giuliano Vivaldi.

Ilya Budraitskis is a historian, cultural and political activist. Since 2009 he is a Ph.D. student at the Institute for World History, Russian Academy of Science, Moscow. In 2001-2004 he organized Russian activists in mobilizations against the G8 in European and World Social Forums. Since 2011 he has been an activist and spokesperson for Russian Socialist Movement. Budraitskis is a member of editorial board of Moscow Art Magazine and a regular contributor to a number of political and cultural websites and publications.

© 2016 e-flux and the author