Many thanks to our colleagues at Voxeurop for inviting us to republish this interview with Andreas Önnerfors, Professor in Intellectual History in Salzburg, Austria. He specializes in far-right ideology in Europe, radicalisation, and conspiracy theories. His latest book, coedited with André Krouwel, is Europe: continent of conspiracies, an overview of conspiracy theory with contributions by other academics. In this interview he explains the specificities of European conspiracism and which theories specifically target the EU. A fuller description of the book can be found at the end of this article.

Peggy Corlin for Voxeurop: The title of your book is Europe : continent of conspiracies. Are conspiracy theories more widespread in Europe than elsewhere?

Andreas Önnerfors: No, it is different. There has been an overfocus on how conspiracy theories have shaped American politics since 1776 [the American Declaration of Independence, editor’s note], and of the paranoid style of American politics during the McCarthyism years, the Iran-Contra affair, since 9/11 and since 2016 with the rise of the QAnon phenomenon. We wanted to investigate whether one could claim there is a parallel to that in Europe. One could say that it is different due to the particular situation of Europe.

What is particular about Europe?

The big difference with America is that conspiracy theories in Europe always include visions of external threat. The Americans have imaginary groups within American society that would wreck that society, be they communists or, for instance, some catholic groups in the 1920s. In Europe, the conspiratorial narrative always includes the idea of a threat coming from outside. There’s a double dynamic: one dynamic which is about internal enemies – gays, lesbians, Freemasons and so on – and the other one which comes from outside – the Muslim Other, the Jewish Other, the Russian Other – and all wanting to dissolve the unity of Europe.

Are the EU institutions or the EU itself targeted by conspiracy theories?

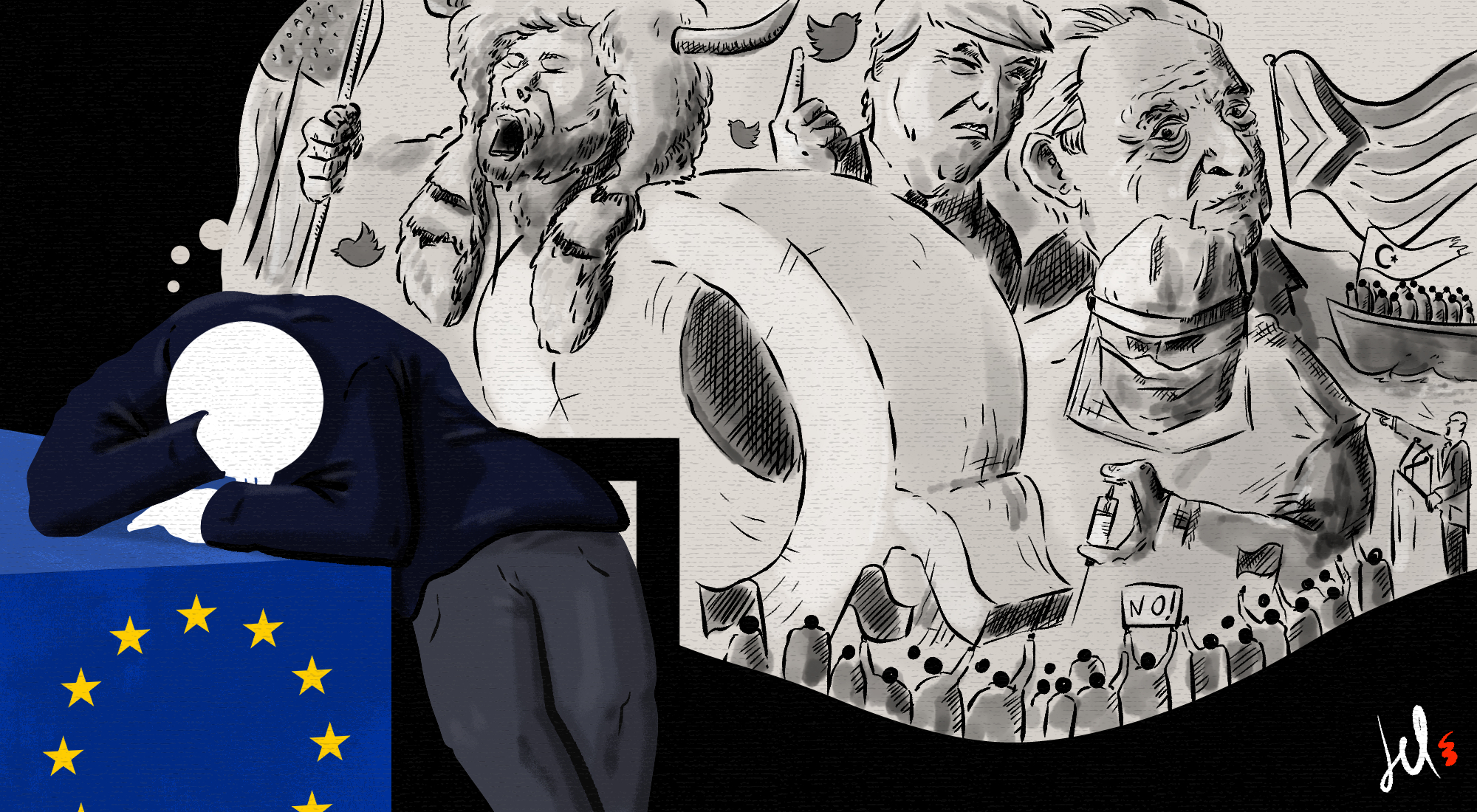

The first two chapters of our book are about the rising islamophobia in Europe, where populist parties are gaining more and more attraction and where the alleged Muslim invasion – the so-called “great replacement” of French author Renaud Camus – is thematised. Then the so-called ”Kalergi plan” is frequently related as a ”masterplan” for the restructuring of Europe, as the foundational formula of the EU and its institutions, as proof of the ultimate attack against the nation states and their independence. Because in the case of internal enemies, the EU institutions are also part of the plot. They impose a supranational structure that aims at destroying the nation state, the heterosexual family, “traditional values” and so on. It can take different shapes: for some people, the EU institutions foster secular totalitarianism, while for others they are seen as a Vatican attempt of a Catholic takeover. In the Nordic regions, the conspiracy theories about EU institutions are based around a fear that a Catholic wave is destroying Nordic freedom and independence. It has also fuelled Brexit in Britain, where a foreign culture of law, institutions and policymaking is perceived as a threat.

Conspiracy theories can also lead to mass murders, like the attacks committed by Anders Breivik in Norway in 2011. How is that?

Anders Breivik carried out this attack 10 years ago. One chapter of our book is specifically about the Eurabia theory. According to that theory, internal and external enemies are collaborating : the Liberals and the Feminists work hand in hand with radical muslims in the Middle East to bring in people and invade Europe, and to destroy the independence of national states and Europe’s Christian values. In that theory all kind of muslim immigration is portrayed as an act of hostility, like in the words of Renaud Camus. My chapter of the book shows how these ideas have become terrorist manifestos, like in Breivik’s case, but also in the 2019 attack of the Halle synagogue, in Germany [2 people got killed], and the one carried out in 2020 in Hanau, in Germany again, where 10 people were killed in shisha bars. A new variety of Eurabia theories has recently been developed, according to which Europeans are being replaced by nasty outsiders and Jews are behind this, and this replacement is controlled by somebody else.

Are some EU member states more targeted than others?

Yes, our book shows that Germany is a particular target. For many different reasons. It started during the Greek debt crisis when Germany stepped in and kind of tried to dictate how the Greek economy should recover. In the Greek media, the EU was suddenly portayed as a continuation of the Nazi regime, a Fourth Reich run by the Germans. That idea has been picked up by Russian disinformation. In the Brexit debate, Germany has been also targeted as wanting to control and dominate European politics, again as a continuation of the Nazi regime.

Who promotes these theories?

There are groups which benefit from them: Populist political actors both from the right and the left. Because one key ingredient of the populist message is the idea of an elite versus the people. A strong leader speaks on behalf of the people and channels an antagonism between the people and the elite. As we have seen during the last decade, it is right-wing populist movements in particular that draw from conspiracy theories. Because you can single out the experts, the rule of law, supranational decision-making or the “political class” as your key enemy, and that attracts a lot of people. So, conspiracy theories make sense in various domestic political settings, be it Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece, the AfD in Germany, the Rassemblement National in France or the Brexit campaign in the UK. The other point is that conspiracy theories are used by foreign actors as part of disinformation operations. Russia is the origin of lots of these narratives, and China to a lesser extent. But the main actors are those media outlets and social media that are loyal to the Russian government. Because conspiracy theories are very powerful: you can implant them as an explanation of ongoing political events and thereby undermine your political opponents. It’s a cheap way of doing so because it’s on the level of narrative. This narrative level is becoming more and more important. And from outside the EU there is also QAnon, which has started to invade the European debate, particularly within the Covid-sceptic movement.

Are there some regions in Europe where conspiracy theories are more widespread?

It depends on what you want to analyse. Regarding countries that are vulnerable to Russian disinformation you can see, for instance, that in early July’s general election in Moldova the anti-EU camp was peddling conspiracy theories against the European Union and Western liberal values. The same goes for Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and the dispute about the anti-LGBT+ laws. That kind of narrative, that connects the LGBT+ with conspiratorial European values, is very strong in South-Eastern Europe. There is a belt, from Poland down to the Black Sea, where there is an alternative interpretation of what European values are. In that region Russian disinformation campaigns are strongly present. Regarding anti-vaxxer and Covid denialism, these are very strong from Berlin to London, where hundreds of thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest. There’s also a similarly active movement in Denmark. So it’s difficult to say conspiracy theories are stronger here or there. We have to look at each kind of narrative separately.

Are there some specific events that have prompted conspiracy theories during recent years?

Yes. Conspiracy theories always follow crisis in Europe. If you have a crisis people want answers: why does it happen? Conspiracy theories are great because they not only explain the facts, they also explain the ethics behind them. You always get an answer about whose responsibility it is, who has done something bad. This is the pattern we have seen over the last ten years. When we had a global financial crisis, it was easy to accuse the international capital and globalists of manipulating the economy. Then the refugee crisis became a perfect terrain of imagination, with some people believing that this could not happen by chance, that somebody was steering it. And now we have Covid, which is a perfect object for various explanatory narratives.

Conspiracy theories are now bringing together a wide range of people in anti-Covid protests…

Yes, it’s surprising how the anti-corona protests have managed to unite people from different camps. Specifically, a greenish alternative-left camp and a traditional nationalist authoritarian camp. In the case of Germany for instance, the two groups are suddenly on the stage together, hugging each other. The conspiratorial mindset has somehow become not only a union of the extremes but also somewhat mainstream. Right-wing skinheads march with climate activists against the government, which is perceived as the big threat. This is something new.

Are conspiracy theories dangerous?

Yes, for sure. There is a difference of what ideals of politics we have. If we think that politics should be driven by passions then we can better accept expressions of rage and fear, since passion is part of political mobilisation within a democracy. Alternatively, if we see democracy as based on reason, then we have the rule of law and experts preparing the basis for sound decision-making. This is a key opposition in democracy. What do we want? A politics of passion or a politics of reason ? Conspiracy theories are dangerous because they place 100% of their weight on the politics of passion. There is nothing rational about conspiracy theories. They try to mimic rational arguments, but these can be debunked. They would never withstand a trial in court, or the scientific method. The politics of reason gets derailed. When, for instance, during the Brexit campaign, Britain’s High Court judges were called “enemies of the people”, the politics of passion was getting really dangerous. We have seen during the Covid protests in Berlin, and of course with the 6th of January in Washington DC [the assault on Capitol Hill by supporters of Donald Trump] the meaning of the idea that violence is a tool to attack and bring down our politicians. The Covid protests are very dangerous.

Andreas Önnerfors is Professor in Intellectual History at the University of Salzburg. He and André Krouwel have just published Europe: continent of conspiracies (Routledge, 2021), an edited volume investigating the impact of conspiracy theories on the understanding of Europe as a geopolitical entity as well as an imagined political and cultural space. Focusing on recent developments, the individual chapters explore a range of conspiratorial positions related to Europe. In the current climate of fear and threat, new and old imaginaries of conspiracies such as Islamophobia and anti-Semitism have been mobilised. A dystopian or even apocalyptic image of Europe in terminal decline is evoked in Eastern European and particularly by Russian pro-Kremlin media, while the EU emerges as a screen upon which several narratives of conspiracy are projected trans-nationally, ranging from the Greek debt crisis to migration, Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic. The methodological perspectives applied in this volume range from qualitative discourse and media analysis to quantitative social-psychological approaches, and there are a number of national and transnational case studies.

Peggy Corlin is a French freelance journalist who writes on economic and social affairs for print and online media. She has contributed to Channel 4 News in France, AlterEcoPus, Liaisons Sociales Magazine, Entreprise et Carrières, Planetlabor.com, and Voxeurop.